This article mainly shares some details from the travel and other related matters that weren’t covered in the "Itinerary". There are also many practical tips included!

(Actually, we didn't do much planning ourselves. Most of it came from the helpful suggestions of some friends in online forums. Special thanks to everyone for their enthusiastic support!)

About Transportation

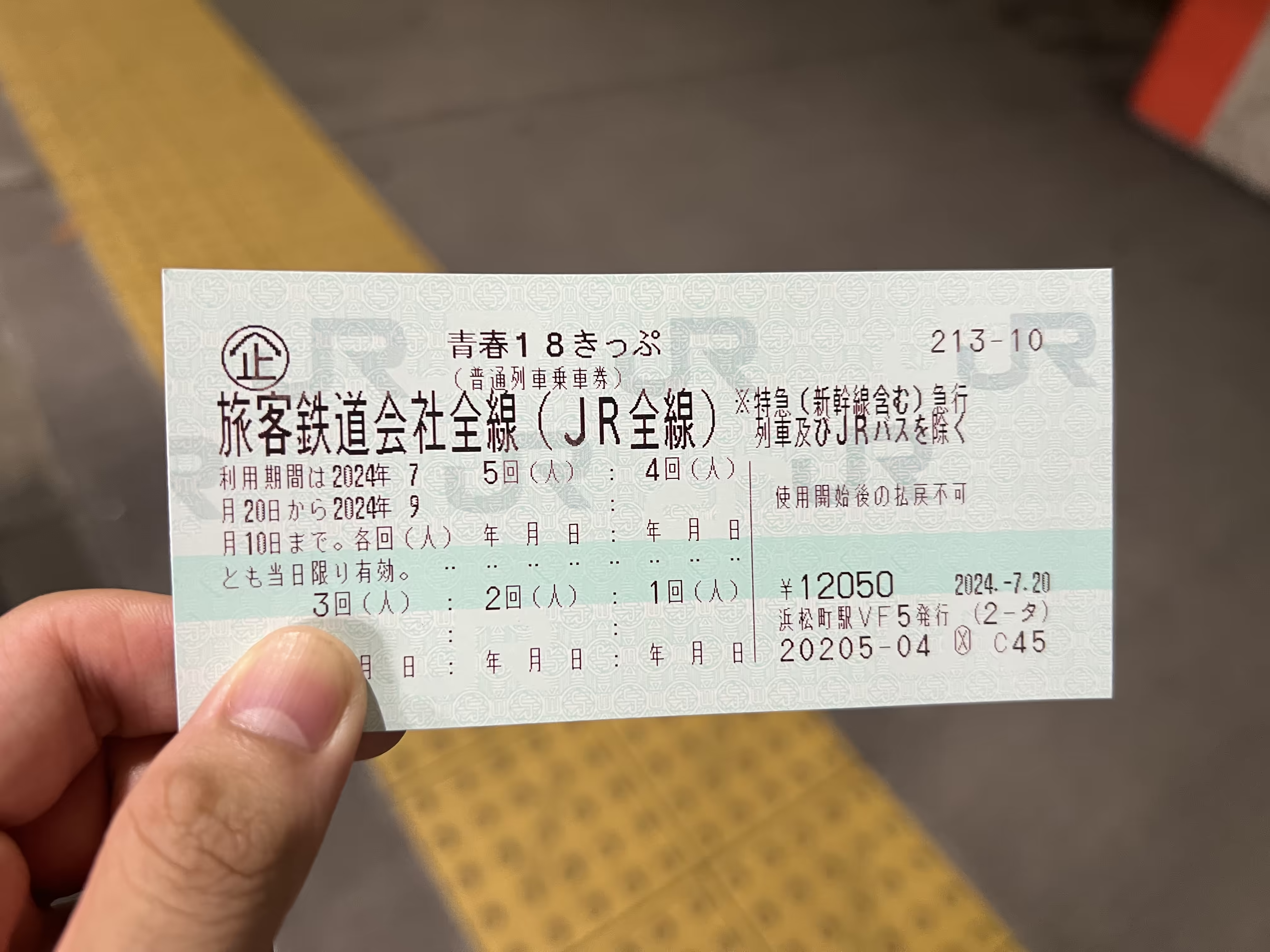

Long-distance transportation includes high-speed trains (although my friend prefers regular trains) and flights. We tried to choose cheaper options for high-speed trains and flights, and flights were mostly with budget airlines. For instance, the flight from Nagasaki to Narita cost only around 300 CNY for a 1,000 km journey, which was quite shocking. For domestic travel in Japan, we mainly relied on JR trains, supplemented by other local transportation options like metro systems and buses. We bought a "Seishun 18" ticket, which could be used by up to 5 people/times/day for ordinary and rapid JR trains (but not express or limited express trains, or JR buses). This was a great way to save money on long-distance JR travels compared to using IC cards. We probably should have bought two "Seishun 18" tickets and researched more travel tips to save even more money, but we didn't have time to explore further.

When taking long-distance JR trains, be mindful of whether you're crossing regions, such as from JR East to JR Central, or JR West, as these are considered separate zones. If you're crossing these boundaries, you need to buy separate tickets or get assistance from station staff for recalculating the fare(精算) when using IC cards. Many small stations don't have staff, so you have to be careful! In addition, although Nagasaki is in the Kyushu region, it's a different zone from other parts of Kyushu, and you need to purchase tickets or get your IC card fare recalculated at certain stations.

As for the Shinkansen (bullet train), it used to be worth it with the JR Pass, but after the price hike, it's no longer as economical. Using the JR Pass or buying a regular ticket for the Shinkansen can be quite expensive, so it's not really in line with "budget travel" anymore (as two poor college students, we felt pretty uncomfortable with the cost). Taking a taxi is out of the question—Japanese taxis are notorious for their high fares.

About Accommodation

Some of our hotels were booked in advance, while others were reserved a few days before (as our plans evolved during the travel). One night was a last-minute booking due to an unexpected situation. In general, it's always better to book early. The average cost was around 130 CNY/person/night because we split the cost with my friend, making it cheaper than if we had booked separately. Also, our hotels were all close to train stations (駅前), so I have to praise my friend's skills in finding convenient places to stay.

The quality of the hotels varied. The best accommodations were in Nagasaki and Nagoya, where we had private bathrooms, balconies, and full kitchen appliances (though we didn't cook much). The next tier of hotels didn't have private stoves or microwaves, but each floor had a shared kitchen, and private bathrooms were still available. The more basic hotels had shared bathrooms and public showers. The worst was a small room with no soundproofing, a bunk bed, and shared bathrooms (we had to change floors to shower). That was the hotel we had to book urgently in Shizuoka due to an unexpected situation. The absolute worst was the capsule hotel, which had the smallest space of all. The reason for staying in capsule hotel is that on weekends and holidays(土日祝), hotel prices will be two or three times higher than on weekdays(平日), especially in Tokyo. If you are poor, you can only make do like this.

Additionally, Japanese hotels charge the "accommodation tax"(宿泊税), which varies by region. In the regions where we stayed, Kyoto and Fukuoka were the only places that charged this tax regardless of the price of the room (for us, it was only 200 JPY per person). Other places also have accommodation taxes, but if the room price is below a certain threshold (e.g., in Osaka, if the room costs under 7,000 JPY per night, no tax is charged), they don't impose the tax. For more details, you can check each prefecture's website regarding accommodation taxes.

Some hotels or inns require you to remove your shoes when entering (土足厳禁). You'll need to store them in a designated area. Some hotels were so outrageous that they charged extra for showers (for example, in Yokohama, the shower room was 100 JPY for 4 minutes—let's just say we chose to skip the shower).

The Unexpected Incident on July 22nd. Originally, we planned to stay near the West Fuji Station in a guesthouse. After booking on Booking.com, my friend found that the same hotel was cheaper on the Qunar platform, so he canceled the Booking.com reservation and re-booked on Qunar. However, Qunar was actually booking through Booking.com again, and it mistakenly used the canceled reservation number as the new one. As a result, we couldn't check in at the hotel. We had no choice but to quickly rebook a hotel in Shizuoka and head there, which meant we missed seeing Mount Fuji. Fortunately, the hotel in Shizuoka was still affordable, and later, Qunar refunded us and compensated for the extra transportation costs. So this did not significantly impact the rest of our trip.

About Language & Communication / Social Atmosphere

This was one of our biggest concerns at the beginning. I finished learning JLPT N5 last year but hadn't touched it for a year, and my English is far from fluent. My friend, on the other hand, was on another level—he couldn't even fully remember the hiragana and katakana charts, and his English wasn't great either. He pretty much relied on a translation app (which honestly made me admire his courage for originally planning to travel to Japan alone). However, as the trip went on, I found that most of our communication went smoothly. I managed with simple Japanese combined with slightly more complex English (my grammar was a mess, but as long as I could get the words out and make them understood, it worked). We only had to use the translation app in a few cases, like when the other person didn't understand English at all. My friend handled most of the itinerary planning and hotel bookings, while I took care of communication, so we made up for each other's weaknesses.

During the hotel booking mishap in Fujinomiya, I had to call Booking.com's customer service and communicate in English the whole time. My grammar was a mess, but I got my point across, and the issue was resolved. At that moment, I felt like my English-speaking skills had reached MAX level.

Social atmosphere. All the Japanese service staff we encountered were incredibly polite, always greeting us with smiles and treating us with great respect. In fact, after returning to Shanghai, the contrast was so stark that we felt a bit uncomfortable when dealing with casually indifferent restaurant staff. When crossing the street, most people would wait for the traffic light. (I did see a few Japanese salarymen jaywalking late at night in Nagasaki, but it was rare.) If there was no traffic light at a pedestrian crossing, people could walk straight across, and cars were required to yield unless pedestrians signaled for them to go first. Not once did we see a car trying to cut in front of pedestrians—this was completely different from China. On buses, the driver would verbally announce every action—departing, turning, stopping. Every passenger who tapped their IC card (whether boarding or alighting) would be acknowledged with a “thank you” from the driver. Their way of speaking often extended the final "su" sound in polite phrases like "ます~." On subways and JR trains, it depended on the crowd. If there were many people, you could hear some quiet conversations, but if the train wasn't crowded, it was almost completely silent. Of course, if there were babies on board, crying was unavoidable—but at least during our entire trip, we never once encountered anyone blasting videos or music on their phones like you sometimes see on Chinese subways or high-speed trains.

However, all this comes at a price. Japan's social atmosphere is noticeably more restrained compared to China, especially in the workplace. Interactions between people don't feel as casual or natural. While drivers in China don't always yield to pedestrians, people accept that they have the right to cross against the light when it's safe. And while service workers in Japan are exceedingly polite, this also means they have to suppress their emotions to a greater extent. In the end, every system has its trade-offs.

There were a lot of foreign tourists in Japan, with Chinese tourists being the most common—no surprise there. Every day, we'd run into at least five fellow Chinese travelers. One interesting encounter happened in Toyohashi. An elderly man carrying multiple bags approached us and spoke directly in Chinese to ask for directions. (He didn't look like a tourist—our guess was that he was an empty-nester from China who had come to Japan to visit his children.) Speaking of which, one of the easiest ways to tell apart Japanese and Chinese people in summer is by looking at whether they wear shorts. Most Japanese men still wear long pants in summer, which would absolutely roast me if I had to do the same. (So yeah, our outfits made it pretty easy for Japanese people to recognize that we were Chinese.)

About Prices & Payment Methods

Japan's prices aren't as outrageously high as Hong Kong's, but they are definitely more expensive than in mainland China.

Meals: We didn't splurge much on fancy meals throughout the travel (which is why I barely mentioned food in my itinerary recap). When looking at restaurant menus, we usually skipped anything priced above 1,000 JPY (about 47 CNY at the time). Instead, we mostly went for set meals (定食) and frequently ate at chain restaurants like Yoshinoya, Sukiya, and Matsuya. One day, we even had oyakodon (chicken & egg rice bowl) at what seemed like a welfare center (probably a nursing home, which my friend found). And sometimes if it got too late, we'd just grab a supermarket bento(弁当) for dinner. Then there was Saizeriya. My friend made me eat at Saizeriya multiple times—first in Shanghai, then again in Japan. I had never eaten at Saizeriya before this travel, and now I've had so much that I'm sick of it. Absolutely ridiculous. For breakfast, we bought bread from convenience stores or supermarkets the night before. My friend is a total "bread monster"—he'd have one as a midnight snack, another for breakfast, and yet another during the day. He easily ate two to three times more bread than I did. Our itinerary was rich in experiences, but our meals were… pretty basic (lol).

One evening, while buying a bento at a supermarket in Osaka, an old man suddenly came up to us and said, “八時から半額” (From 8 p.m., these will be half-price). He even pointed out which section would have discounts. I was amazed that I understood him and quickly thanked him. Turning around, I saw that there were already many elderly people in the supermarket. They had already selected their products and were waiting to line up to check out at 8 p.m. (So this is what they call a “slum supermarket” in Osaka, huh…?)

General Prices: For drinks: vending machines > convenience stores > supermarkets. Whenever we spotted a supermarket, we'd stock up on bottled water. Speaking of convenience stores, they are everywhere in Japan, more common than standalone trash bins (seriously, Japan has almost no public trash bins except near vending machines and inside convenience stores/train stations). But hotels do provide trash bins, so we often ended up stuffing them to the brim. Convenience stores in Japan are truly "convenient", but the prices are higher than supermarkets. We often go to 711, Lawson, and Family Mart to buy supplies, and we usually buy bread from them (so we really ate a lot of different kinds of bread along the way).

Japan offers a variety of payment options: cash, bank cards (VISA, MC, JCB, etc.), transportation IC, ID card, and various payment methods such as PayPay. WeChat Pay and Alipay is also quite popular, and is supported by convenience stores (but not by some supermarkets). But it is better to have cards such as VISA and MC. UnionPay cards are not supported by many stores in Japan. In addition, there are cash and transportation IC cards. In fact, as long as you have these two, the payment problem is basically solved. Many vending machines only accept cash. There are many types of transportation IC cards, such as Suica for JR East and ICOCA for JR West. Of course, IC cards are universal throughout the country, so you only need one. If you use an iPhone, you can add a Suica/ICOCA to your Apple Wallet and top it up with a linked card (even UnionPay), making things even more convenient.

When using non-Japanese bank cards to withdraw cash from ATMs in Japan, the UnionPay card withdrawal fee at convenience store ATMs is very high (my friend has fallen into this trap twice). It is best to use VISA, MC and other cards to withdraw cash. Even if a fee is charged, it will not be very high. Another thing is to withdraw more cash at a time. The more money and the fewer times you withdraw, the less the fee loss.

About Products(GUZI, Comics & Figures)

Don't buy figures in Akihabara—they're overpriced as hell. You're better off getting second-hand ones from Xianyu (闲鱼). Instead, visit stores in smaller cities like Hiroshima, Kitakyushu, and Fukuoka for better prices. My friend insisted on visiting Animate, BookOff, and Surugaya in every city. I nearly got sick of browsing (seriously, enough already). Yet, we rarely found anything truly worth buying. However, Animate in Nipponbashi (Osaka) is great for manga—they stock a lot of classics and popular series. If I go to Osaka again, I'd definitely visit it again.

Some stores have "GUZI bargain bins" where you can dig for cheap goods. In Shinjuku, we found a discounted Project Sekai golden foil card. But most of the time, you'll just find leftovers after all the good stuff has been picked clean (so frustrating). (Pro tip: If you see a store highly recommended on Xiaohongshu (小红书), chances are it's already been raided—beware of the Xiaohongshu paradox!)

I bought manga in Nara, Osaka, and Fukuoka, a cheap figure in Fukuoka, and some random goods in Shinjuku and Osaka.

My friend bought a 300 JPY bargain-bin Hoshino Ai figure in Kitakyushu, plus some manga and other goods. [White Miku (白葱, Snow Miku) is highly sought after in any anime goods store, so unless it's crazy expensive, it gets snatched up fast. My friend finally found a reasonably priced one.]

We didn't buy too much, fearing airline baggage restrictions. We only had 7kg of free carry-on and were traveling backpack-only, no suitcases. Turns out, airlines barely check backpack weight—they mainly check suitcases. Maybe they know backpacks can only get so heavy.

About Oto-games / Arcade Games

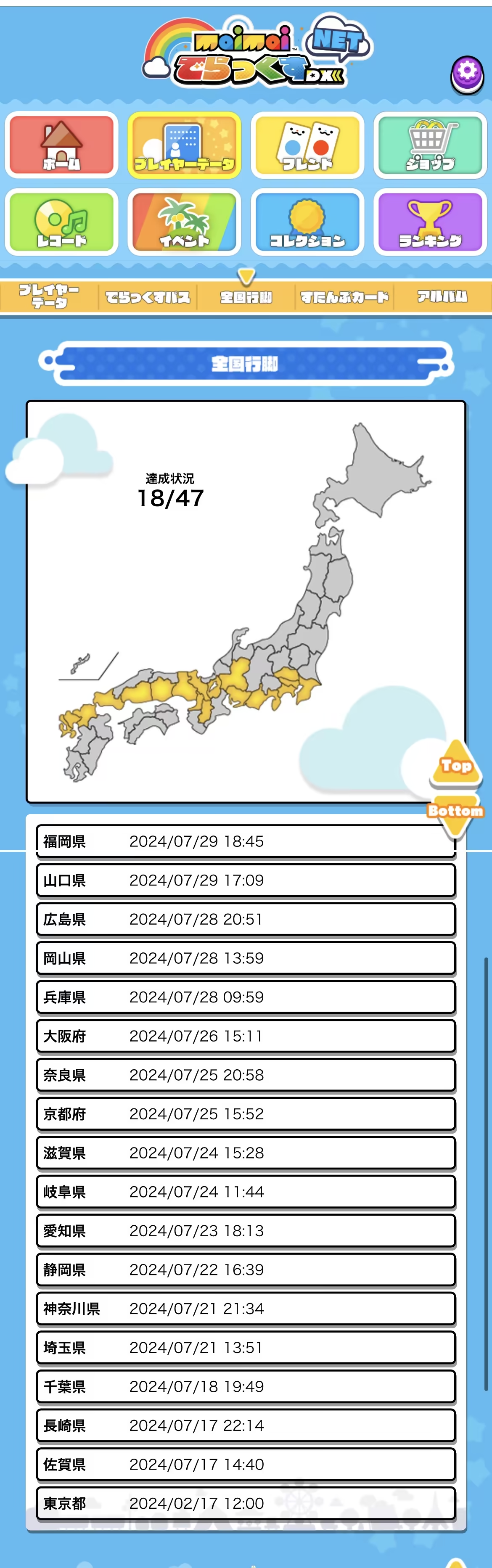

As everyone knows, I'm a maimai fanatic, and I met my travel companion (a schoolmate) through maimai. So playing oto-games (rhythm games) in Japan was a must, and we made sure to play a maimaiDX round in every prefecture we visited (feels like we were revealing our true intentions, lol).

About arcades: Round1, GiGO, and other arcade chains are the most common, followed by some other companies' arcades. Every arcade is typically equipped with maimaiDX, CHUNITHM, and ONGEKI (except for some particularly small arcades, like the ones in Chichibu and Shimonoseki). The number of maimaiDX machines usually ranges from 1 to 10, with most arcades having around 3 to 6 machines. CHUNITHM usually has 2 to 12 machines, with a maximum of 14. ONGEKI usually has 2 to 8, with a maximum of 10. The key difference compared to China is that oto-game arcades are everywhere in Japan, and the number of machines is high, meaning you rarely have to wait in long lines (but of course, there's a trade-off, each game costs a fixed 100 JPY, whereas in China, it's generally cheaper).

Many arcades support electronic payments (電子決済できます), and there are two main types: 1. Some arcades pay SBGA to integrate electronic payment options directly into the machines and game systems, usually allowing payments via transportation IC cards. 2. Other arcades install separate payment devices, avoiding extra fees from SBGA. These also support transportation IC cards, and some even support Alipay+ (allowing you to scan with Alipay CN), which is super convenient. However, from our observations, Round1's maimaiDX machines do not support electronic payments (not sure about other oto-games). GiGO arcades, being Sega-owned, generally have built-in electronic payment options. That said, it's always best to carry some cash, as you can exchange bills for coins at the arcade's currency exchange machines (両替).

I have to say, playing on Japanese maimaiDX machines is just amazing! Even though I personally prefer the inner screen, I could still feel how much better the condition of the Japanese machines was. The biggest surprise was that I achieved a "gold rating" in 39 games (this was in a Nara arcade, which had insanely well-maintained machines, such a great experience!). My friend even managed to get a "rainbow rating" with ease.

In Kokura (Kitakyushu), we found that the arcade had live streaming setups for many oto-games. It helped record my friend's gameplay, and later, he even found the livestream replay on YouTube. First time being on a live stream—felt a little embarrassed, lol.

There were also CHUNITHM and ONGEKI.

CHUNITHM: Playing on Japan's 120Hz screen machines was unbelievably smooth! I've improved quite a bit, now getting S ranks on simpler level 8-9 red charts.

ONGEKI: Not my strongest game, I can only clear level 8 yellow charts with around SS ranks. One highlight was that we arrived just in time for ONGEKI's 6th anniversary (July 26th). Starting from the 26th, logging in daily earned you an SSR character card, with a total of six available. But since we left on the 31st, we only managed to get five out of six—so close!

ONGEKI has an annoying A/B mode system: B mode is the standard one—100 JPY per play, fixed three-song set. A mode, however, is more restrictive: If you pay 100 or 200 JPY, you get fewer points and fewer songs. Only if you pay 300 JPY, do you get the same value as B mode (plus a 10-point bonus for unlocking purple charts). Arcades can freely switch between A and B mode, but players can only switch from B to A—not the other way around. (Super frustrating.) Special shoutout to Nagoya arcades, the worst ONGEKI experience—every machine we encountered was locked in A mode. Absolute pain. (Now I understand why this game remains a Japan-exclusive—between SBGA's policies and the games with pay-to-win features, it would be hard to introduce it elsewhere, especially in mainland China.)

And finally, the big event—Card Maker!

We both got the character "Acid (childhood version)"(アシッド 幼少期)DX PASS—such a popular and gorgeous card. And in a stroke of luck, I pulled the CHUNITHM Nai (ナイ) card. We also printed all five of our ONGEKI anniversary SSR cards, plus my friend even printed a whole batch of cards for others (dude was basically running a card-printing factory at that point, lol).

In case of any discrepancy between the English and Chinese blogs, the Chinese blogs shall prevail.

Attention: The comment sections of Chinese and English articles are not interoperable.